Hartley News Online Your alumni and supporter magazine

The University of Southampton Special Collections team has produced a series of blog posts detailing University developments through time, as seen through our archives. This post, originally shared on their blog, explores the world of Rag: student-run, fundraising events and organisations that have been part of student life for over 100 years.

The name ‘Rag’ is rather obscure, and no-one is entirely sure of its origins. The Oxford English Dictionary describes the act of ragging as “an extensive display of noisy disorderly conduct, carried on in defiance of authority or discipline”. The thought is that early fundraisers may have ‘ragged’ passers-by until they donated.

Another idea is that the word came from the Victorian era, when students took time out of their studies to collect rags to clothe the poor. More recently, ‘backronyms’ have been invented – including ‘Raise and Give’, ‘Raise a Grand’, or ‘Raising and Giving’ – to emphasise the philanthropic aspect of the activities.

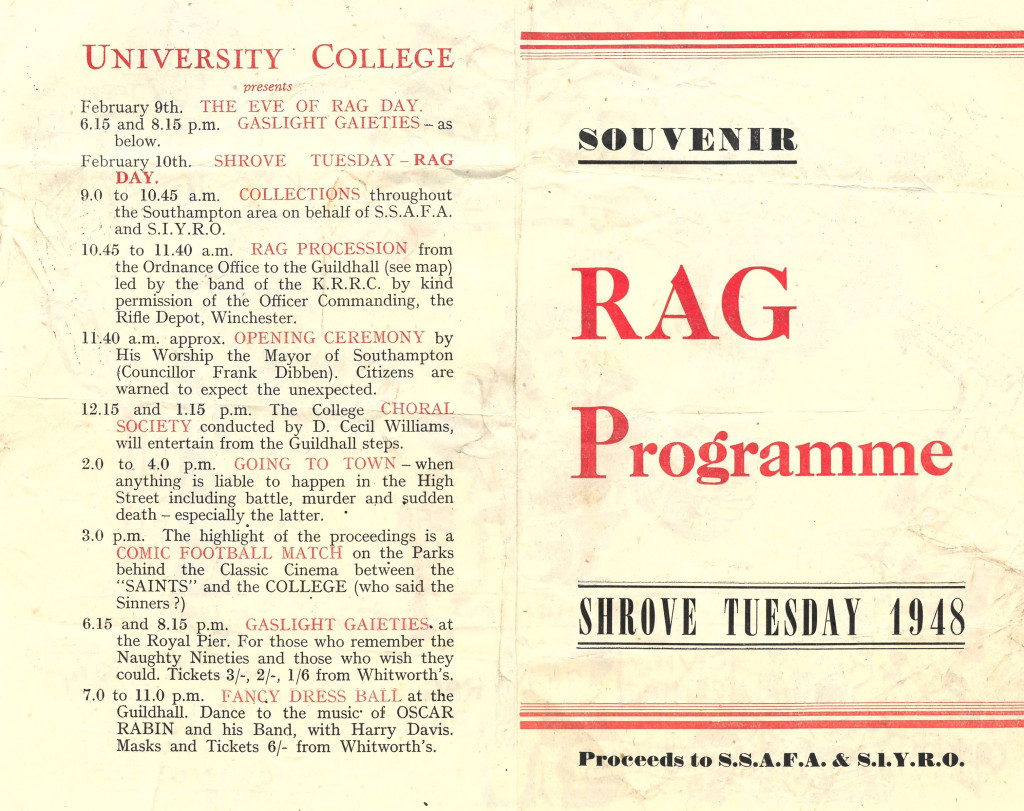

Rag has been part of University life in Southampton since at least the 1920s. Alumnus Peter Smith describes how it was “a highlight of the winter term, and it was always held on Shrove Tuesday, as if to get the festivities over before the strictures of Lent”. Over the years, it has consisted of a variety of activities, ostensibly aimed at raising money for charity, including a procession, ball, a show, and the publication and sale of a ‘Rag mag’. As the years progressed, the antics became progressively wild. And, as you might imagine, the event has not always existed in harmony with Southampton residents.

A key feature of Rag was the publication of a ‘Rag mag’, a small booklet traditionally filled with politically incorrect humour sold in the lead up to Rag Day. The earliest Rag mag in the University Collection is a copy of Rag Bag dating from 1927. Over the years, Rag has been abolished and revived on a number of occasions. Its revival in 1948 was followed by the publication of Goblio, the longest running Rag mag in the collection, with copies dating from 1949-64. From 1967, the University’s Rag mag took on a range of titles, including Son of Goblio, Babel, Southampton City Rag, Flush, Dragon, and Southampton Students Stag Rag.

Apparently, the 1958 edition of the Goblio was banned, and later ritually burned at the Bargate. Consensus among the students was that this was an extreme response, with one recounting how the Goblio “was certainly rude and scurrilous, largely satirical, but rarely offensive”. While these magazines might be considered tame by today’s standards, times have changed, and we struggled to find any jokes we felt appropriate – or funny enough – to share. Copies of the Rag mags are available in Hartley Library – found in the University Collection in the Open Access area of Special Collections.

For many years, an afternoon procession was a key part of the Rag. Decorated floats on lorries lent by local firms, complete with ‘Rag Queen’ (usually a local girl), would parade through the town, providing entertainment and collecting money.

The Engineering Society was always very prominent during Rag, often accompanied by their human skeleton mascot ‘Kelly’ and their 1920s vintage open single-decker charabanc called ‘Toastrack’. In 1948, they are reported to have produced a 60-foot dragon for the parade!

Other events have included an annual Rag ball with dancing and fancy dress at the Guildhall and a Rag show with a revue format.

Obviously a key aspect of Rag – maybe more so for some years than others – has been raising money. The University has chosen various charities over the years. In 1927, “all money (less Rag expenses)” supported the children’s summer camps organised by the Rotary Club of Southampton. In the years following the Second World War, the festivities were called the Gaslight Gaieties, and the money went to the Armed Forces Charity, formerly known as the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Families Association.

In 1958, the chosen charities were Dr Barnardo’s Homes, British Empire Rheumatism Council, National Society for Cancer Relief, and the Handicraft and Social Centre for the Blind. A Students’ Union handbook from the 1950s reported that sums raised in recent years ranged from £800 to £1,400.

As with all university cities, there has not always been harmony between ‘town and gown’, and over the years, Rag has been a point of conflict. R G Smith, an engineering student here in the 1940s, recalls “jovial goings-on, which were enjoyed both by ourselves and the citizenry of Southampton […] dressed as Long John Silver complete with parrot, I ‘held up’ the Ordnance Survey Office with a fearsome-looking horse pistol, and stung the personnel there for contribution to the Rag charity collections”. We wonder if Southampton residents have the same cheery memories of the Rag as Mr Smith?

It is clear that, at times, Rag events did get out of hand. Alumna Olive, who was a student here in the early 1960s, describes the attempt to establish a ‘Charities Week Appeal’ in November 1961 “to distinguish from its infamous predecessor ‘Rag’”. She describes how there was “a genuine attempt to get away from the unpleasant features of Rag, and to concentrate on the worthwhile task of collecting money for local good causes”.

Things did not exactly go to plan. Olive gives the details: “The whole thing looked as if it was going to be too quiet and respectable until Students’ Council decided to ban Goblio. A packed Union meeting confirmed their decision, and inevitably it was reported in the local and national press, radio, and television.

“As there is no such thing as bad publicity, £900 net was raised for charity. For the first time, there were no letters of complaint, either to the University or the local press.”

Despite best endeavours, it was difficult to disassociate the fundraising from the pranks, and ‘the annual flour and water fight’ still took place in Charities Week – although Olive reports positively that “no hard feelings and a good deal of hard cash (£1,450) for charities resulted”.

Southampton students have organised various stunts over the years. In the early years – when trams still ran through the town centre – the students used to process into town, stopping traffic and collecting money.

As the years progress, the stunts got more elaborate and extreme. Various former students have recollected: a banner appearing overnight down the Civic Centre clock tower; a cannon being lifted from one of the Winchester army establishments by residents from Connaught Hall; painted footsteps leading from Lord Palmerston’s statue in Romsey Square to the nearby lavatory; the ‘kidnap for ransom’ of a top Southampton Football Club player; and a banner proclaiming Rag draped over Stonehenge. Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight was broken into by a group of Southampton students as a publicity stunt. The Rag of 1963 featured a transatlantic advertisement as the Queen Mary sailed for New York with Rag painted on her stern; apparently, Cunard were very understanding!

In the 21st century, Rag has become the major fundraising committee of the University. Along with volunteers, they spend the year raising money for dozens of charities – and recently supported the Office of Development and Alumni Relations’ £25m campaign to build the Centre for Cancer Immunology. Events include speed dating in February, hitch-hiking events to Christmas markets, and the ‘Big Give’. Don’t worry if this all sounds a little tame compared with the antics of previous decades – there’s still the option of getting your kit off for the annual Rag calendar!

It’s not possible to calculate the amount raised for charity by Southampton Rags, but whatever the total, it is inspiring to think about all the good causes that have benefited from Southampton’s students over the years, and the many more thousands of pounds that will be raised in the future.

You can read subsequent posts in the series – and explore other archive content – on the University of Southampton Special Collections blog.

Did you take part in Rag when you were at Southampton? If so, we’d love to hear from you! Email us your fundraising stories at alumni@southampton.ac.uk