In September 1789, Taylor was pleased when parliament suspended making a decision on the question of the slave trade until its next session, hoping that what he saw as ‘the madness’ of abolitionism would subside in the interim. He began to rehearse several proslavery arguments that became familiar themes in the planter defence of slave trading and of slavery, claiming that abolitionists knew nothing of life in the Caribbean colonies and that they painted a false picture of how enslave people were treated. Taylor also began to consider the possible implications of an abolition of the slave trade, stating that he would ‘stock’ his estates with slaves from Africa in case the supply should soon end and claiming that British planters in Jamaica were prepared to migrate to French Saint Domingue (Hispaniola) in the event of an abolition bill passing in parliament.

[…] I see the House of Commons proceeded some way in the slave trade as they call it, and then agreed to deferr their deliberations untill the next year. I hope the madness will go off with the dogg days, and that they will begin to think more of their own affairs, and leave the princes of Guinea to take care of theirs. The more they know of the value it is of to themselves, the more they ought to encourage it, and as for ever making the coast of Africa a commercial country they had better take care of their own, which would be entirely annihilated but for that to the East and West Indies, and Africa. Mr Pitt must have strange ideas in his head to imagine, that a sett of priests, madmen, and here and there a banker that never was out of England, can know any thing of trade and commerce, or what is so proper for a distant colony as the people themselves do. The thing that should be done is to make these people prove their assertions by facts, and who the particular people are, that uses the barbarities they talk of, to give the individuals that are attacked an opportunity of clearing themselves, or of punishing their calumniator in a court of law. I am very glad to find that we have so many friends in the House, and that he [Pitt] could not carry his friend Willberforce’s schemes into execution, for Sir William Dolben’s insiduous [sic] regulations I wish both those gentlemen would take a passage to the West Indies themselves, and see how negroes are treated, and then go to the coast of Guinea and see how happy they live there. I will buy as many negroes as I well can find out of every ship that comes in, and stock myself as well as I can, but I am and I believe most people in case the trade should be abolished are determined to migrate with their negroes to Hispaniola, for we may as well be under an arbitrary government at once, as to be under one that avowedly pretends to direct our cultivation, and prevent our making what use of our property we ourselves chuse, after having invited or rather decoyed us away by charters and Acts of Parliament. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1789/25, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 6 September 1789)

Tag Archives: William Dolben

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 16 April 1789

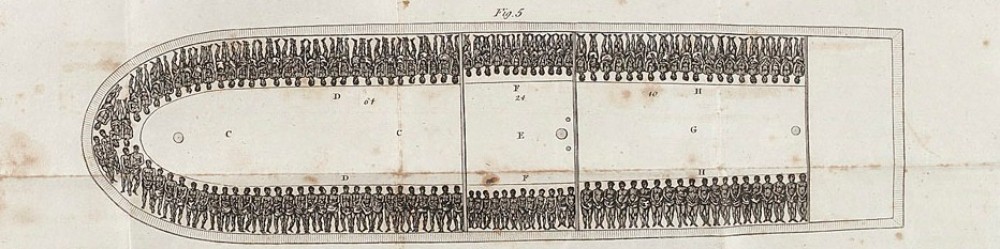

During 1788, parliament received hundreds of petitions from across the country calling for the immediate abolition of the slave trade. In same year, a bill by the abolitionist MP, William Dolben, had imposed regulations on slave traders to do with space and conditions on the Middle Passage between Africa and the Caribbean. By 1789, William Wilberforce was preparing to introduce a bill to the House of Commons for the outright abolition of the trade. In this private letter to his friend and fellow plantation owner, Chaloner Arcedeckne, Taylor set out his opposition to Wilberforce and the abolitionists, using proslavery arguments that were to become familiar parts of the debate over the future of the British slave system.

I am favoured with yours of 2 March and I assure you that all ranks of people in this country are sincerely glad of the King’s recovery, and wish him a long and happy reign […] I hope that this event will prove favourable to us in the negroe business, and am happy to hear we are likely to have good and powerfull friends, who will stem the torrent. It is very surprising that Mr Wilberforce who cannot be in the least acquainted with the West Indies, or the nature of negroes, should be so strenuous in wishing to make laws for the treatment of them, and I declare before God that after a constant residence of 29 years in this country, I have never heard of one tenth of the ill treatment that they say negroes meet with, or of iron coffins, nor of putting pepper upon a negroe after he has been punished or whipped. Five and twenty or thirty years ago negroes were infinitely harsher treated, than they have been since, and I positively aver that negroes are infinitely happier than the peasantry in any part of England, and there is hardly a week passes that a negroe does not do with impunity, what would hang a white man at home. I really do not think that the trade can possibly be carried on under the regulations it is at present under, that some regulations were necessary, it was certain for any boy from school was sent as a doctor of a Guinea man, and they ought not to have been allowed to crowd the ships as they did, but to putt them under such restraints as they have is certainly destruction to the most valuable and lucrative trade they have. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1789/5, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 16 April 1789)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Holland, 30 August 1788

Writing from Holland, his sugar estate, in August 1788, Taylor reflected on a successful bill by the abolitionist MP, William Dolben, imposing regulations on slave traders regarding space and conditions on board ships transporting enslaved people on the Middle Passage between Africa and the Caribbean. Later that year, the Jamaican Assembly accepted this as an act ‘founded in justice, humanity, and necessity’, but here Taylor rails against it, drawing comparisons between the supposed ignorance of its framers and of the enslaved victims of the Middle Passage.

[…] Messrs Longs write me on the 11 July that a bill had passed the Lords for the regulating the number of slaves that a ship should take in on the coast of Guinea, according to her tonnage, that alone is I think an abolition to the African trade, and seals our ruin for the framers of the law, and passers of it know as little what is the proper number for a ship to carry, as a new negroe himself does, and altho I have not seen it, nor do I know the number yett apprehended it will be such a restriction, as will amount to a prohibition […] Can they think or imagine this trade lost, the West India planters and merchants ruined, that they will ever be able again to establish it even if they have the islands left them, & that any man will ever again confide in their proclamations from their Kings, or Acts of Parliament, or any British subject migrate 3000 miles from home to risque their lives and toil for a country to have then a sett of fanaticks and rascally negroes take away their property, and endanger their lives, or will they not rather go among any other European subjects where their industry will be encouraged, and where in place of being villified, will be protected, while they do not act contrary to the laws of the place, or attempt to subvert the government thereof. Such a phrensy I believe never struck any people but madmen before, and none of Don Quixotts [sic] exploits are to be compared to it. Succeeding times will never believe that a nation brought almost to beggary by a debt of £220,000,000 […] should run the risque of losing near £2,000,000 stg revenue p ann, the consumption of about 1500,000 of her manufacturies annually, and the employment of 400 sail of ships, and the employment of the necessary artifices employed about them, and bringing the materialls to them, and the whole to please a sett of mad enthusiasts, and about 2000 vagabonds originally slaves in their own country, and not one of whom had ever acquired £100 by his own manual labour. Indeed I think our fate is as much decided by the bill past [sic], as it can be any other way, and I forsee every step, and the ruin approaching, and which will inevitably befall us if this bill is not repealed in the very beginning of the session, there will be no further investigation of the matter necessary, this is the coup de grace to the colonies, the ruin of the merchants, & the manufactureis depending on them and in the end the ruin of Britain. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1788/21, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Holland, 30 August 1788)