At the end of 1787, Taylor commented on proposals by Matthew Boulton, the British entrepreneur and manufacture of steam engines, to adapt steam power to sugar mills in Jamaica. He was not fully convinced by them.

[…] Respecting Mr Bolton, untill he sends out modell, & letts people know the premium he expects for his machines, and convinces them they will answer, he will gett no encouragement here, I should think if he was so certain of the success, that he would wish to have one erected on an estate even at his own expence, to be reimbursed should it answer, or leave to take his materials away if it did not, and that would convince people of its utility, for at present we here have only his own ipse dixit [i.e. unproven assertion]. As you justly observe sending out only one man is nothing, we want nothing new from him, but his mode of applying the steam to the turning the mill, the method of hanging his boiler to the most advantage to save coal, for machinery work and making the mill we know more about it than he does, or can be expected to know, and if once any person steals that mode from him, all his expectation from this island is at an end, as there is not patent that does, or can extend to this country. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1787/20, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 6 December 1787)

Tag Archives: Chaloner Arcedeckne

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 1 May 1787

Taylor’s discussion of breadfruit relates to the infamous 1787 expedition of the HMS Bounty, commanded by Captain William Bligh, to collect plants in Tahiti and introduce them to the West Indies, where it was anticipated that they would help provided food for the enslaved people on sugar estates and other properties. Taylor’s discussion on this point leads into a discussion of his continuing mistrust of the British government’s policies towards the British-Caribbean colonies and speculation about the degree to which Jamaica might achieve self-sufficiency in food and clothing.

[…] The bread fruit would certainly be an addition to our negroe provisions, but a hurricane would certainly blow of [sic] the fruit, as well as either break the trees, or blow them up by the roots, but tho they are liable to that, they still would be of very essential service to us, tho I do not believe Mr Pitt cares a farthing if all Jamaica the Windward Islands and the inhabitants of them were annihilated so that he could but gett a revenue from them. […] [I] am afraid to buy any new negroes untill the hurricane months are over and we see how the blast affects the young canes and sprouts. […] there seems to be a system adopted by the British legislature to extirpate the cultivation of the cane in the British West India colonies, and consequently to force us to live upon our internall resources, and have recourse to the manufacturing our own cloathing from our cotton, and to have no connexion with the mother country at all, if it is so, the late hurricanes have cooperated wonderfull well with its plan, and they will in the course of the next seven years see their scheme so farr carried into execution that this island will hardly be able to be considered as a sugar colony, as the proprietors will not be able to carry that manufacture on, and the iron foundries copper smiths and manufacturers whose dependence is on the trade to the West Indies and the coast of Africa will have leisure to employ themselves otherwise. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1787/5, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 1 May 1787)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 11 October 1786

Taylor’s brother died of a fever, although the evidence available in Taylor’s letters does not allow for a more precise diagnosis of his illness. Here, Taylor reflects on the medical treatment that his brother received, on his own health, and on the preponderance of sickliness among whites in Jamaica. He also discusses the debts of Sir Charles Price, an extraordinarily wealthy and influential local sugar magnate, who died in 1772, leaving his heirs with a heavily indebted estate.

[…] I apprehend his doctor mistook his [Sir John Taylor, Simon Taylor’s brother] case, and gave him gouty medicines, when I believe the medicine he wanted ought to have been to expell bile which is the greatest and almost sole disorder of this country. We have both of us lived so long as to see very good numbers of our old friends and acquaintances drop off. I hardly know now twenty people in the island, that I knew when I first came here. […] I do not believe Sir Charles Prices debt will be recovered, he owes me upwards of two thousand pounds which I look on to be lost I am pretty well again after a slight fever I have had a few days ago, by getting cold, indeed almost every person in this part of the island have been sick, from the excessive heat of the weather in the middle of the day, with cold mornings & evenings, the weather is also drier about this town than I ever remember it in my life in October, which used to be constantly wett […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1784/19, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 11 October 1786)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 1 June 1786

The 1780s were a transformative decade in Taylor’s life. The American War and its aftermath transformed his political outlook towards a distrust of the British government in London, a perspective that became more entrenched with the advent of the parliamentary campaign against the slave trade in 1788. His sugar estates were adversely affected by the several hurricanes that hit Jamaica in the first half of the 1780s, and a fire devastated the works of his estate at Lyssons in 1784. His elder brother, Sir John Taylor, died on a visit to Jamaica from England in May 1786. Thereafter, Taylor assumed the role of head of the Taylor family, managing the plantation that belonged to his late brother’s wife, Lady Elizabeth Taylor, in western Jamaican, and making his brother’s son, Sir Simon Richard Brissett Taylor, his principal heir.

[…] I have had the misfortune to have lost my poor brother, who was taken ill at his estate down to leeward, and I believe by some mismanagement of his doctors thrown into a dropsy, on which I advised him to come up in a man of warr that was at Lucea to this town which he did but was so far gone that his life could not be saved, and he died on the 6th of last month. His death has been a very severe stroke on me, as well as his little family, which I must now take all the care of that I can, indeed they are so very young just now, that they will be for some years but with their mother, and I must endeavour to settle my matters so as to go home three or 4 years hence, when I have gott rid of the effects of the fire, the hurricane, and dry weather and other calamities that have pursued me for these three years past, and can make an arrangement of my brothers affairs, which will give me a great deal of trouble and fatigue. His wifes estate lying 150 miles from this town, I have been obliged to go there since his death, I must go there again the middle of this month, and must visitt them twice a year for there is really no person in that part of the country that there is the least dependance to be putt in, and that added to my other business will give me enough to do God knows. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1786/9, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 1 June 1786)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 10 October 1783

By the end of 1783, Taylor expressed his satisfaction with work at Golden Grove, under the supervision of the overseer, Madden. Taylor described his plans for improving the cultivation and productivity of Golden Grove, which included the purchase of more enslaved workers and the avoidance of ‘jumping crops’, which were years of heightened productivity created by managers and overseers who overworked enslaved people more than Taylor thought was advisable in order to impress absentee proprietors with a large and lucrative crop.

[…] Madden seems to me to go on very well, you have as industrious, and good sett of white people there as at any estate in the island, and your negroes are healthy and well and abounding in provisions, there are 40 acres in cocos untouched, which I reserve for new negroes, and in case of a hurricane, the next thing I must begin on is to fence off some land next Hampton Court to put into guinea grass as a beginning to keep up your cattle & by & bye [sic] when I have enough to keep what steers I shall reserve for the plough to hole your land with that instrument shall begin that method, and do away with jobbing, the new negroes I have lately bought for you are well, after buying one more lott of men, I must then think of buying some Eboe women, the estate is now coming on into its proper train, and I think that it will hardly in future make less than 600 hdds provided that no jumping crops are made, which by distressing, and harassing both negroes and stock, as well as throwing the estate back, takes three years again to bring matters into their proper channell again […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1783/38, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Lyssons, 10 October 1783)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 10 October 1783

In 1784, James Ramsay published his famous and influential Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies. Ramsay had lived as an Anglican clergyman in the British-Caribbean colony of St Kitts (hence Taylor’s comment here about the Windward Islands in the eastern Caribbean) and drew on his experience there to condemn the licentious violence and abuses of the British slave system. Although he did not advocate the abolition of slavery, Ramsay did publish plans for the abolition of the slave trade, and his work inspired the early abolition movement. In this letter it is clear that Taylor has learned of Ramsay’s proposals, probably from Chaloner Arcedeckne, months before the publication of the Essay, suggesting either that Ramsay’s ideas were well known by the end of 1783 or that one of Taylor’s correspondents was a close associate of the abolitionist. Taylor’s initial reaction to Ramsay’s critique seeks to paint a rosy picture of slave life on the plantations and foreshadows the proslavery arguments that planters developed in the years to follow, during their disputes with abolitionists.

[…] I do not apprehend that Mr Ramsays schemes will be of any effect many of the best negroes on almost all estates are Christened, and no one opposes it whenever they deserve it neither do we find them the worse for it, but in general better, & I remember hearing formerly a good deal of the Code Noir of the French I procured the book, & on examination of it with the negroe laws of this island found very little difference how their laws are in our Windward Islands I do not know, but upon all the well regulated estates in this island, the negroes live infinitely better than the poor people in many parts of England, they have no care for tomorrow, if sick have a doctor & maintainance [sic] from their masters are clothed by them, and in times of scarcity are fed, they breed as much small stock & hoggs as they please, & sell them to whom they please, as also plantains, yams, cocos, &c […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1783/38, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Lyssons, 10 October 1783)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 26 June 1783

Taylor, despite his loyalty to Britain before and during the American War, was disillusioned with British policy by 1783 and believed that the remaining American colonies, such as Jamaica, were over taxed and abused by the metropole. He assessed the island’s prospects of becoming more self-sufficient with regard to clothing and livestock as well as speculating that white Jamaican colonists were so disillusioned with the empire that they might now think twice before rushing to defend the island from a foreign invasion.

I really think that the time is not farr of that will force us to sett about making our own cloathing ourselves, as for cattle there has been a very large number of penns lately settled, and many more are settling, and as the sugar works are thrown up they must begin some manufacture to employ the negroes. […] this country was loaded with taxes last year to the amount of £24000 which is to be paid this, for forts fortifications and the expences of the last martial law, and I cannot conceive what they want to do now with forts and fortifications, except they intend to send out an army to garrison them for they surely cannot be mad enough to think there is a man in the island who will be stupid enough to risque his life, or have his property destroyed, or his slaves carried off, to promote the benefitt, or to live under the protection, and contribute to support the revenue of a country who has so damnably oppressed us as Britain has lately done, and who have behaved so inconsistently with common sense, as in on session to give us charity, and at the same time burden us with a tax of £500000 stg p ann, can they conceive that we are so wanting in common sense, as not to think we consider ourselves but as the potters ass & will give the same answer he did, who when his cruel master wanted him to run from an enemy replies, can I ever gett a crueller master than you have been to me and therefore I do not care to whom I belong. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1783/23, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 26 June 1783)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 1 June 1783

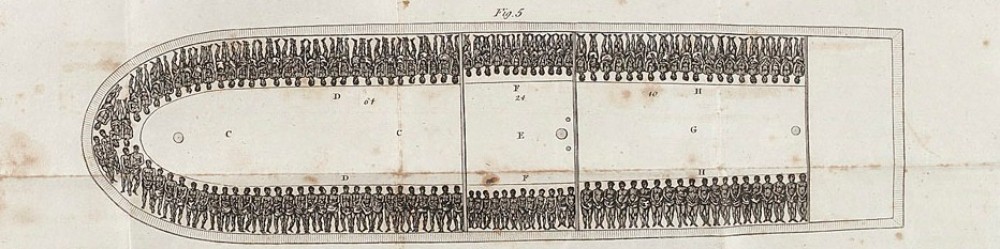

Economic prospects for Taylor and Arcedeckne improved with the ending of the war. Taylor laid out his plans for buying more enslaved workers from the next ‘Guinea man’ (slave ship) to arrive from ‘a good’ part of Africa and indicated that slaves from Africa were in much demand across the Caribbean. He noted that the enslaved people living on Arcedeckne’s property were in good health (before commenting on the state of the livestock), and his letter details some of the many tasks and jobs involved in maintaining a sugar estate.

[…] there will not be any danger or your negroes wanting a belly full, and there is plenty for new negroes as soon as any Guinea man from a good country arrives, many ships have been expected but there has as yett but few arrived from their having stopped at St. Thomas’s and there disposed of their cargos for to supply the French and Spaniards […] as soon as negroes come in I must buy as many as I can for you, untill I gett 30 this year, and when I can buy payable in 1785 I must again gett 30 more for there is really plenty of work for them in clearing and billing your pastures which are really foul at the estate, and making fences and planting the rocky parts into Guinea Grass, for it is absolutely necessary to have pasturage as canes, from the looks of your people a man would hardly know them they are so much altered in their looks for the better, the cattle are in good working order but not so fatt as I could wish, the mules are in good order and from every appearance there ought to be a good crop […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1783/19, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 1 June 1783)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 30 March 1783

Taylor’s comments here illustrate how far the uncertainties of war hampered planning in plantation management. With the cessation of hostilities, much remained to be decided, but Taylor felt relieved and able to make plans for the future, which included the purchase of enslaved Africans for Golden Grove.

I would upon the presumption of a peace, have bought you a doz. of negroes lately, but I considered that sugars would sell very low indeed for the first year, did not know what terms the peace was to be made, and was very diffident what to do, but now thank God that blessed event has happened we can with ease and safety with prudent management go on improving every year, and adding to the strength yearly.

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1783/12, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 30 March 1783)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 24 February 1783

After taking full control of Arcedeckne’s Jamaican properties from John Kelly, Taylor sought to reassure his friend that they would be well managed. This extract illustrates how far the sugar estates relied upon a large and healthy enslaved workforce and aspects of the economic relationship between livestock rearing farms, or pens, and the estates. Both Taylor and Arcedeckne owned pens, which served the needs of their estates for cattle.

I do intend as soon as it is convenient to begin to buy the negroes you consent to and will endeavour to bring your estate into proper order at the least expense possible, you have been very ill used indeed for had the negroes you had bought been taken care of, you would have had nearly enough for every purpose, but it is too late now to repine, and will not mend matters. In regard to the penn near Spanish Town the great use it will be of to you, will be to draw off the old cattle annually from the estate and penn at Batchelors hall as soon as the crop is ended which is about Aug. and when there is generally good grass, and as soon as they get fatt to sell them off before the dry weather setts in, that will save your opening the land at Ventures at least for a time while the war continues, for it is by no means prudent to send negroes there at present for fear of their being stole off by the Spanish privateers.

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1783/9, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 24 February 1783)