Taylor commented to George Hibbert on the failure of Wilberforce’s abolition bill to pass the House of Lords in 1804. By this time, he was fully aware that such a setback would be unlikely to deter future efforts by his political adversaries. He claimed, however, that if the British state were compelled to pay financial compensation to British-Caribbean slaveholders, on the basis of purported commercial losses, then abolition would be unaffordable and, therefore, impossible. He also reiterated the by now familiar commercial argument against abolition, mentioning to Hibbert the calculations that he had been making about the value of West Indian trade to Britain, seeking to clarify the extent to which the mother country benefitted from and depended on the colonies. Lord Stanhope was a keen supporter of abolition, and he married his second wife, Louisa, in 1781. Taylor’s comments about her display the longstanding depth of antipathy that he harboured for those who professed antislavery views. Conversely, Taylor was impressed by the Duke of Clarence (who became King William IV in 1830).

I am favoured with yours of 4 July. I perfectly agree with you that the House of Lords have given Mr Willberforce a check, but I do believe his persevering Spiritt and that of the Gang he is connected with will never lett the Question rest untill they find that an abolition and full Compensation shall be awarded us for the Injuries our Properties will sustain, and when ever they find that their Humanity will will [sic] oblige them to putt their hands into the Pocketts it will vanish away. Lord Stanhope is and ever was a mad man, I remember him in 1792 and an expression his wife made use of that she wished that the Negroes would rise and murder every white Person in the Islands. It is a really [sic] pitty she had not been in St. Domingo since that time to this and she would have held a very different Language. The Duke of Clarence I believe has been very indefatigable in collecting information on the Subject and knows it better than most Men in the upper House. I do not thing think there are ten Men in either that know the benifitts that accrue to the British from the West India Trade, therefore I have been very anxious to know what the Actual Imports and Exports to every part of the World under their distinct Kingdoms and what was and has been the Imports and Exports to and from the West Indies both the old Islands and the Conquered ones and then it would be seen what a very considerable part of the Trade of Britain depends on the Island [sic] and how much she is benifitted by them.

(Taylor Family Papers, I/G/3, Simon Taylor to George Hibbert, Kingston, 29 August 1804)

Category Archives: Trade

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 5 December 1792

At the end of 1792, Taylor wrote to tell Arcedeckne about his fear at the prospect of an end to the slave trade. The Jamaican assembly had produced a report, laying out their opposition to abolition and emphasising the economic value of the current slave system to the mother country. Such economic arguments were an important part of the proslavery defence of the slave trade, but as this letter also shows, constitutional arguments and claims about property rights were also important. The Jamaican assembly claimed that parliament had no right to pass legislation that would affect the internal affairs of Jamaica (as they claimed that the abolition of the slave trade would) and argued that slaveholders should receive financial compensation for any parliamentary measure that might affect their business interests. Taylor also sought to place the current imperial crisis over slavery in the context of the dispute that led to the American Revolution, claiming that Prime Minister Pitt’s political ally, William Grenville, was continuing the policies introduced by his father, George Grenville, during the 1760s.

[…] We are very much afraid here respecting the abolition, and should have petitioned the Crown on it, but it was found that it was as unparliamentary to petition the Crown upon any matter pending in Parliament, but I have sent you a copy of a report made by a committee of the House [the Jamaican assembly], which shews from authentick facts, that if the trade is abolished, that shall not be the only suffers [sic], and claim as our right our having our properties paid for, and disclaim their having any right to legislate internally for us, for my own part I am hopefull when this report goes home, and getts into the hands of dispationate [sic] men, that they will see their interest is too much involved in it, to suffer the minister to wantonly throw away so very a beneficial commerce, as that of the West Indies […] As for Pitt, I have no hopes from him, he is led by that cursed fellow Grenville, who and whose father have ever been the bitter enemies of the colonies, and to whom the loss of America from the British Empire is to be attributed, he first alienated the minds of the people there from Britain, and has in a great manner done the same here, and when hatred once begins, separation is not a great way behind. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1792/14, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Spanish Town, 5 December 1792)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 17 January 1791

As the abolition debate continued, Taylor’s frustration rose and his language grew more colourful. In his view, abolitionists were behaving unreasonably by interfering with a lucrative system that he thought was best left to the oversight and management of slave-traders and slaveholders. His reference to events in the French islands is probably to the failed insurrection by free people of colour in Saint-Domingue, led by Vincent Ogé, seeking legal equality with whites.

[…] I do not think peace will be of any long continuance but it seems this unhappy country [Jamaica] is never to be at rest and I consider the British minister to be a more inveterate enemy to us than the French or Spanish nation, I see that the miscreant Wilberforce has begun upon the slave business again, if they mean nothing why do they plague us but they are so ignorant and obstinate they do not nor will not hear truth or reason, reason tells every one to be humane to everything under him but they will not allow us to have common sense. Reason tells them not to grate and harrass [sic] the minds of people that give them a revenue of a million & a half yearly & feeds 600,000 of her inhabitants but envy says no I will annihilate you I will suck the blood from your vitals […] a day may come and he [Prime Minister Pitt] is young enough to live to see it, that England may not have a colony in the West Indies & sink into as despicable a state as it was before it had colonies, & it has been only owing to them & the bigottry, folly & tyranny of Lewes [sic. Louis] the 14th who drove the manufacturers out of his country that she has made the respectable figure she has, for my part I solemnly wish I could dispose of my property here and I would do it at 25 pc less than what it would be valued at, & I would have disposed of it before the scene of robbery and oppression was opened & remove myself and effects to any other country so much do I conceive of Mr Pitts & Mr Wilberforces schemes of benefiting us will imediately [sic] injure me and every one else and I forsee nothing but total ruin will be the upshot of the folly madness & rancour of these two people and their gang, they must have heard what fine doings the madmen of France have provided in the French islands & I hope the blood that has been shed on that occasion may fall on the heads that designed the same for us […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1791/1, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 17 January 1791)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 17 June 1790

Taylor saw the proposal to end the slave trade as a breach of faith between Britain and the colonies of the British West Indies. Despite the apparent impossibility of Jamaica seceding from the British empire in the same manner as the thirteen mainland colonies during the American Revolution (due to the reliance of white colonists on British armed forces to protect them from slave rebellions and foreign invasion and on protected British markets for their exports), Taylor persistently discussed the prospect during the first months of the abolition debates in parliament. Whether he was in earnest or privately venting his frustration at British attitudes towards the planters is a subject for speculation.

[…] We are by no means desirous or willing to separate from Britain, but for my part, if the slave trade is abolished, or putt on such a footing, as that we cannot have negroes on at least as good terms as other nations, I shall that moment wish the separation to take place that instant, and for ever. As for their faith, it is as much derided as the Punica Tides. Where is faith to be putt in a nation that gave charters, and passed Acts of Parliament to encourage the African Trade for negroes, and proclamations for people to settle the islands, and embark their all in those undertakings, and then to abuse the people they have deluded, and wish to stop the trade by which only they can carry on their settlements, where is their faith that the emigrants under those proclamations should enjoy every priviledge of Britons, and then pass Acts of Parliament to establish courts of amiralty [sic], where property is to be tried without a jury. Where was their faith to entice the emigrants from America to go and settle on the Mosquito Shore [evacuated in 1786 in agreement with the Spanish], and then give the place to the Spaniards. Where their faith to sell lands in Tobago, Dominica, St Vincents and Granada, and now to abolish the African trade, but to cheat the people out of purchase money. If they call this faith, I do not know what faith is, but think the true name is robbery, villainy, and swindling in the highest degree. If they once arrive at a separation, and expect they will have the supplying us with manufacturies, they will be greatly mistaken, do they supply Hispaniola and the French islands with linnens, woolens, iron mongery, coppers, stills &c or ships to carry home their productions. They know they do not, nor never did. Do they supply any articles to America that are ever paid for, their merchants will tell them no; and every one who has trusted them is ruined, and if they chuse to carry on trade without returns, they may have custom enough. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1790/18, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 17 June 1790)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 5 August 1789

By August 1789, Taylor expressed relief that the question of abolishing the slave trade had been stalled by a parliamentary enquiry. He conceded to Arcedeckne that some sorts of regulations to the trade might be acceptable but also began to further stake out his argument that ending the slave trade would lead to the ruin of the British-Caribbean colonies and – ultimately – of Britain itself. Taylor combined this economic argument with his opinion that parliament’s discussion of abolition amounted to a breach of trust towards the colonists of the West Indies.

[…] I see our great question was not decided, and the event was precarious. It has been the maddest piece of work since the crusades and I am very glad to see so many respectable people have taken up the matter, if regulations are made in the mode of purchasing slaves on the coast, so as those regulations do not tend to prohibit the trade, we can have no objection to it, but to abolish it, is ruin to us, and ultimately to them. I see they go on very slowly in their examination of evidence, and I suppose when the House meets on a call, they will putt it off untill the next session. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1789/23, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 5 August 1789)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 5 July 1789

By July 1789, the House of Commons had launched an inquiry to the slave trade. Wilberforce made his first speech on the subject in May of that year, and it was clear that he had the support of his friend, Prime Minister William Pitt. Taylor was incensed by these turns of events in England and perceived them as part of a conspiracy against the West Indian colonies, reflecting back on the rise in the sugar duties in 1781 and claiming that British ministries had been pursuing oppressive policies against the colonies for nearly three decades. Rich in bombast,Taylor’s letter provides an insight into white colonial slaveholding perspectives on the transforming British attitude towards slavery and slaveholding.

[…] I shall be very glad to see a favourable upshot to the great question, for I believe it involves in it, whether Britain will have any sugar colonies or not, for if that trade is abolished, there will be no occasion for the naturall enemies of Great Britain to assemble any great fleets or armies, as a few frigates and troops will be sufficient, as not one will be mad enough to oppose any who ever chuses to deliver us from a nation who treats us as Pharoah did the Israelites, wanting them to make bricks without straw, and the only difference is they want us to make sugar without negroes, and negroes are as necessary to make sugar, as the straw was to burn the bricks. If they want to see the light that their exploits in America are held in, they ought to read the debates in the new congress, and there they will see in what detestation they are held there, and what they may expect from that quarter in case of a warr, can they suppose that the West Indians and inhabitants of the colonies can have any veneration or regard to a nation, that has for 29 years been continually adding burden upon burden upon them, and adding insult to injustice, as in 1781 they gave to the sufferers by the hurricane £40000 in charity, and laid an import on the staple of £500,000 in perpetuity, and now are loading us with the most opprobious names their malice can invent of devills, monsters, bloodthirsty thieves, kiddnappers, &c, &c, &c. Notwithstanding Mr Pitts and Lord Sheffields argument, that the duties on sugars would be the same whether they were made in the French or other foreign islands, yett are they sure those foreign enemies would trade on the coast of Africa with British manufacturers, would they send home the sugars in English bottoms, or their own, or use in their islands British manufactures, in that case what is to become of their shipping, shipwrights, or manufacturers. I shall be very glad to see the report of the Privy Councill, and shall be glad to find that the Bill is thrown out of the House. As for foreign nations giving up the trade, they have not the least idea of it, and instead of that are now giving a bounty on negroes imported into their colonies. I cannot conceive what can have occasioned Mr Pitts resentment against us, if they will lett us alone, we ourselves know what are the proper regulations, and they will be made with time, as for regulations for our internal police, it would be only the blind leading the blind, and no one will permitt them to chalk out the rules how we are to raise our staples, or what particular ones we will follow […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1789/19, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 5 July 1789)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 16 April 1789

During 1788, parliament received hundreds of petitions from across the country calling for the immediate abolition of the slave trade. In same year, a bill by the abolitionist MP, William Dolben, had imposed regulations on slave traders to do with space and conditions on the Middle Passage between Africa and the Caribbean. By 1789, William Wilberforce was preparing to introduce a bill to the House of Commons for the outright abolition of the trade. In this private letter to his friend and fellow plantation owner, Chaloner Arcedeckne, Taylor set out his opposition to Wilberforce and the abolitionists, using proslavery arguments that were to become familiar parts of the debate over the future of the British slave system.

I am favoured with yours of 2 March and I assure you that all ranks of people in this country are sincerely glad of the King’s recovery, and wish him a long and happy reign […] I hope that this event will prove favourable to us in the negroe business, and am happy to hear we are likely to have good and powerfull friends, who will stem the torrent. It is very surprising that Mr Wilberforce who cannot be in the least acquainted with the West Indies, or the nature of negroes, should be so strenuous in wishing to make laws for the treatment of them, and I declare before God that after a constant residence of 29 years in this country, I have never heard of one tenth of the ill treatment that they say negroes meet with, or of iron coffins, nor of putting pepper upon a negroe after he has been punished or whipped. Five and twenty or thirty years ago negroes were infinitely harsher treated, than they have been since, and I positively aver that negroes are infinitely happier than the peasantry in any part of England, and there is hardly a week passes that a negroe does not do with impunity, what would hang a white man at home. I really do not think that the trade can possibly be carried on under the regulations it is at present under, that some regulations were necessary, it was certain for any boy from school was sent as a doctor of a Guinea man, and they ought not to have been allowed to crowd the ships as they did, but to putt them under such restraints as they have is certainly destruction to the most valuable and lucrative trade they have. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1789/5, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 16 April 1789)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Holland, 30 August 1788

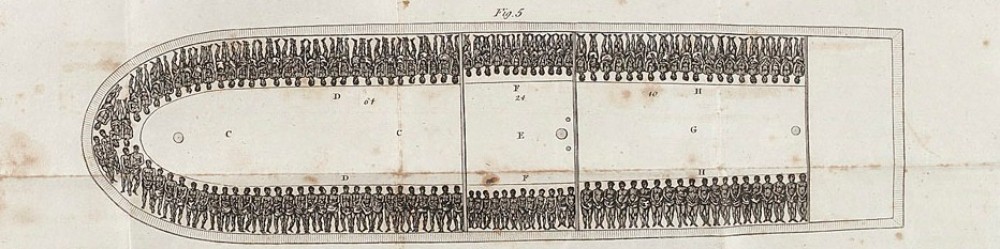

Writing from Holland, his sugar estate, in August 1788, Taylor reflected on a successful bill by the abolitionist MP, William Dolben, imposing regulations on slave traders regarding space and conditions on board ships transporting enslaved people on the Middle Passage between Africa and the Caribbean. Later that year, the Jamaican Assembly accepted this as an act ‘founded in justice, humanity, and necessity’, but here Taylor rails against it, drawing comparisons between the supposed ignorance of its framers and of the enslaved victims of the Middle Passage.

[…] Messrs Longs write me on the 11 July that a bill had passed the Lords for the regulating the number of slaves that a ship should take in on the coast of Guinea, according to her tonnage, that alone is I think an abolition to the African trade, and seals our ruin for the framers of the law, and passers of it know as little what is the proper number for a ship to carry, as a new negroe himself does, and altho I have not seen it, nor do I know the number yett apprehended it will be such a restriction, as will amount to a prohibition […] Can they think or imagine this trade lost, the West India planters and merchants ruined, that they will ever be able again to establish it even if they have the islands left them, & that any man will ever again confide in their proclamations from their Kings, or Acts of Parliament, or any British subject migrate 3000 miles from home to risque their lives and toil for a country to have then a sett of fanaticks and rascally negroes take away their property, and endanger their lives, or will they not rather go among any other European subjects where their industry will be encouraged, and where in place of being villified, will be protected, while they do not act contrary to the laws of the place, or attempt to subvert the government thereof. Such a phrensy I believe never struck any people but madmen before, and none of Don Quixotts [sic] exploits are to be compared to it. Succeeding times will never believe that a nation brought almost to beggary by a debt of £220,000,000 […] should run the risque of losing near £2,000,000 stg revenue p ann, the consumption of about 1500,000 of her manufacturies annually, and the employment of 400 sail of ships, and the employment of the necessary artifices employed about them, and bringing the materialls to them, and the whole to please a sett of mad enthusiasts, and about 2000 vagabonds originally slaves in their own country, and not one of whom had ever acquired £100 by his own manual labour. Indeed I think our fate is as much decided by the bill past [sic], as it can be any other way, and I forsee every step, and the ruin approaching, and which will inevitably befall us if this bill is not repealed in the very beginning of the session, there will be no further investigation of the matter necessary, this is the coup de grace to the colonies, the ruin of the merchants, & the manufactureis depending on them and in the end the ruin of Britain. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1788/21, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Holland, 30 August 1788)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 3 June 1787

Taylor continued to rail against British trade policy throughout the 1780s. He criticised the 1786 Anglo-French commercial treaty, which liberalised aspects of trade between the two nations, and continued to complain about the difficulty of obtaining plantation supplies and about other perceived shortcomings of the post 1783 Atlantic commercial regime.

[…] I sincerely hope the French treaty will fail, for I think it is the coup de grace to the West India colonies by destroying the sale of rum, and to make our case the harder, the damned colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Canada, send their lumber to the English islands, sell their cargoes there, receive the money, and then go to the French free ports, and buy molasses, which is imported duty free, and then distilled into rum for their fisheries. thus our staples are ruined on all sides, and a monopoly against us, even in case of a famine, that we cannot gett the articles of bread, such barbarity is not known even in Morocco. […] I do not know any use that can arise to England by opening a free port in the Bahama Islands, they want no lumber from America, have nothing to send there but cotton, pines & turtle, and they may as well open a free port in Nova Zembla, if there were free ports opened here, and in the other sugar colonies for lumber as staves, boards, shingles, plank, joices, ranging timber, corn, rice, flour, staves and all other articles that the cursed northern colonies cannot send […] and for them in return to take rum, we should derive some benefitt from it, but for that reason I do not expect they will do it. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1787/8, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 3 June 1787)

Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, 19 April 1788

In common with other planters in Jamaica (and across the West Indies) Taylor was taken aback by the popularity and success of the incipient abolition movement in Britain. He contemplated its effects in Jamaica and strongly asserted that he thought an end to the slave trade would result in the economic ruin of the colonies in the West Indies and have negative ramifications for the metropole. He was unsurprised by the involvement of the famous Whig politician Charles James Fox but could not believe that the prime minister, William Pitt, gave his backing to the idea, and he predicted that the proslavery lobby would pick up the support of several prominent spokesmen.

[…] Respecting negroes, I really do not know what to say or write on that subject. If the motion is carried, and a bill passed to prohibit the African Trade, there is an end to the colonies and all concerned with them, for it is impossible to carry them on without them, and I think they will draw on themselves the same destruction as they mean to bring on us, that Mr Fox should do it, is not surprising, but that Mr Pitt should have such an idea excites my utmost astonishment. How are they to replace the revenue at present gott from the colonies, what are they to do with between four and five hundred sail of ships employed in the African trade and to the West Indies, what are to become of the sailors, the manufacturers, the tradesmen the merchants (who have such large debts due them by the colonies) and their wives and families. As for us, they do not seem to think we are the least to be considered in the matter. Butt I suppose there are many people of distinction at home, as the Duke of Chandos, Lord Onslow, Lord Romney and others that will not tamely suffer themselves to be robbed of their property in this most unheard or unthought of before manner. […] Will any man stay in a country where this property is to be arbiraly [sic] taken from him. In case of an invasion by a foreign enemy will any man take up arms to defend that country. The more I consider the matter, the more I am amazed at the madness of it, and the folly and wickedness of the attempt. Things are at present quiet, how long they will continue so, God only knows. but it would have been better had it never been agitated. […]

(Vanneck-Arc/3A/1788/6, Simon Taylor to Chaloner Arcedeckne, Kingston, 19 April 1788)