This post is an expanded version of a comment I made today on the Junto Blog Summer Book Club discussion about Kathleen Brown’s Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, & Anxious Patriarchs. The conversation, led by Joseph Adelman is about the final chapter of the book, on the ‘anxious patriarchs’ of the eighteenth-century Virginian elite. It got me thinking about how the anxieties of this slaveholding elite were related to those of the Jamaican planter class, and – more specifically – to the various worries that Simon Taylor expressed in his letters.

This post is an expanded version of a comment I made today on the Junto Blog Summer Book Club discussion about Kathleen Brown’s Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, & Anxious Patriarchs. The conversation, led by Joseph Adelman is about the final chapter of the book, on the ‘anxious patriarchs’ of the eighteenth-century Virginian elite. It got me thinking about how the anxieties of this slaveholding elite were related to those of the Jamaican planter class, and – more specifically – to the various worries that Simon Taylor expressed in his letters.

Brown’s prescient focus on emotions struck me as interesting. The history of the emotions has come to the fore in recent years. (See, for instance, the AHR Conversation from December 2012). Brown’s work on what historians are now calling an ‘emotional community’ among Virginia planters therefore seems ahead of its time. And it is quite right to zone in on anxiety as the leitmotif in the emotional lives of this elite. Planters were, almost by definition, uneasy creatures – apprehensive about slave uprisings and other threats to their status emanating from within their households or from across the Atlantic.

I wondered how far the careful definitions of paternalism and connections to the Founding Fathers position this not so much as a ‘Virginia book’ (a phrase used in some earlier posts in the Junto Book Club) but as a ‘North America book’. The question of paternalism has been framed by Eugene Genovese’s influential definitions of master-slave relations in the Antebellum South, and it is understandable to want to link a study like this to a discussion of those men of the Virginia elite who shaped the American Revolution. Both of those things help make this a book focused on understanding family, slavery and politics in the region that became the USA.

I have been reading Brown from a different perspective – thinking about Caribbean comparisons. Arguably the real catbird seat in the eighteenth century Atlantic empire was the one occupied by the Caribbean planter class – a wealthier elite than the Virginian and every bit as anxious. It strikes me that as well as thinking forward from Good Wives – towards the Revolution and US South – we can usefully think ‘sideways’, about how this book might serve up suggestions for a further widening of our understanding of colonial planter elites in the eighteenth century . . . including explorations of the gendered social orders, class tensions and emotional landscapes created by planters in other parts of colonial America.

The threat of slave rebellions was more acute in the Caribbean than in Virginia, as were the risks of losing everything to a hurricane or dying from yellow fever. I am not sure though whether the sorts of domestic or political anxieties that Brown discusses in relation to Virginia planters were so much of a consideration for their Jamaican counterparts until the final quarter of the eighteenth century – when metropolitan opposition to planter practices became more apparent. Neither were the men of the Jamaican elite so able to construct an identity based firmly around rural estates – few of them, even those who were resident in the Caribbean, chose to live permanently on semi-industrialised sugar plantations in rural parishes with huge enslaved majorities.

Books and articles by several scholars, including Vincent Brown, Christopher Brown, Trevor Burnard and Andrew O’Shaughnessy, have already improved our understanding of Jamaican and other West Indian slaveholders in relation to their North American counterparts. Could further work on the gendered social order, class tensions and emotional landscapes created by colonial American planters help us towards a better understanding of the eventual fall of Caribbean and Southern slaveholding elites during the nineteenth century? The division of the planter lobby into loyalists and patriots in 1776 was certainly important in those processes of decline and defeat, but planters also failed to defend their vision of the imperial or American future, and their precarious economic and domestic arrangements – the sorts of things that Brown examines in her book – did not manage to withstand the combined pressures of slave resistance, abolitionist scrutiny and federal/imperial scepticism.

My thoughts, having read Brown’s last chapter, are therefore focused on how the practices and actions of anxious patriarchs in eighteenth-century Virginia and Jamaica helped lay the foundations for the fall of their class in the nineteenth century.

Author Archives: cp16v07

Empire's Crossroads

The Caribbean is, and has been, a crossroads in human history. It has been a site of convergence – where people have met, fought, exploited one another, and created new cultures. The incorporation of Caribbean colonies into Western European economies created another sort of crossroads in world history, helping to prompt a ‘great divergence’ in which nations with access to New World colonies and their slave-produced exports were put on a faster path to economic growth than other regions of the globe.

The Caribbean is, and has been, a crossroads in human history. It has been a site of convergence – where people have met, fought, exploited one another, and created new cultures. The incorporation of Caribbean colonies into Western European economies created another sort of crossroads in world history, helping to prompt a ‘great divergence’ in which nations with access to New World colonies and their slave-produced exports were put on a faster path to economic growth than other regions of the globe.

Carrie Gibson’s new book takes a sweeping view of this complicated Caribbean intersection, beginning with its so-called ‘discovery’ by Christopher Columbus in 1492 and taking us up to the present day. It is a bold narrative history of a part of the world that, in many ways, defies synthesis. Precisely because the Caribbean was at a crossroads between various European empires (not to mention the involvement of the USA and, more recently, China) its history criss-crosses with those of Britain, Spain, France, The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and others. Caribbean people speak English, French, Spanish, Dutch and many varieties of Caribbean Creole. Simply defining the region is difficult: are we talking about the whole of the Caribbean littoral, only the islands, or just those parts most affected by the defining experiences of slavery and plantation agriculture?

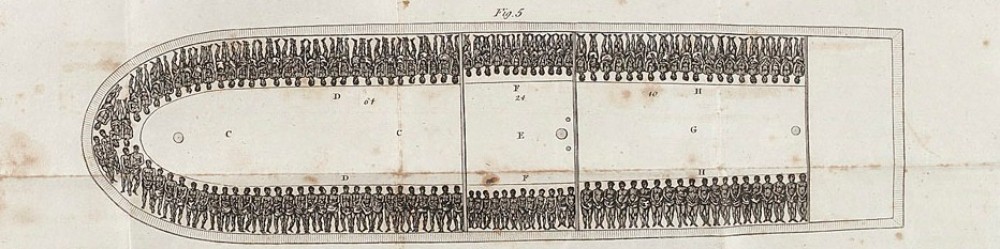

Gibson takes us on a very readable journey through Caribbean history, although it is in some ways surprising that we begin in Western Europe and with Columbus. This is a traditional sort of opening for a book that might well have started in the Caribbean before the arrival of Europeans, or with West Africans – millions of whom were trafficked as slaves to turn the Caribbean into a huge source of wealth and power, not only for individual colonial planters and transatlantic merchants, but for whole European nations. The book goes on to tell the story of the rise and fall of West Indian sugar plantations, slavery and emancipation, nation-building, pan-Africanism, the devastating impact of a Cold War that was not so cold in the Caribbean, different types of migration, and the rise of mass tourism.

This account brings life to its subjects through bold writing and makes use of illuminating quotes and examples. The chapters are divided into subsections that tend to deal with particular regions and events – for instance the chapter on the ending of slavery has sections on the decline of Spain, independent Haiti, slave resistance in the British Caribbean, and American filibustering expeditions. This approach helps bring together the fragmented stories of several different Caribbeans, principally the Hispanic, Francophone and Anglophone, although in places more might have been done to segue between the sections. Gibson’s privileging of narration over explanation left me wishing for a bit more discussion to tease out the wider implications of events and connections between them.

The main strength of Empire’s Crossroads is in its wide vision of Caribbean history. Places like Jamaica, Martinique and the Dominican Republic are dealt with side by side. The Cuban Revolution is presented as a pan-Caribbean event. We also learn about the Caribbean in regional context – about revolutionary relations between Haiti and Venezuela, Martiniquans on the Panama Canal, Jamaicans labouring on Costa Rican banana plantations, as well as the wider Caribbean diasporas of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This type of transnational approach is the mark of an exciting young author whose PhD was about the Haitian Revolution in the Hispanic Caribbean. It certainly helps make this into an original introduction to one of the world’s most complex and fascinating regions.

The Fall of the Planter Class

This is the introduction to a special issue of the journal Atlantic Studies, about the fall of the planters. It argues that the difficulties faced by the planter class in the British West Indies from the 1780s were an early episode in a wider drama of decline for New World plantation economies. The American historian Lowell Ragatz published the first detailed historical account of their fall. His work helped to inform the influential arguments of Eric Williams, which were later challenged by Seymour Drescher. Recent research has begun to offer fresh perspectives on the debate about the decline of the planters. This article discusses that work and maps out new directions in this field. Click here

Full text of accepted manuscript: Petley – Fall of the Planter Class

Gluttony, Excess, and the Fall of the Planter Class

Food and rituals around eating are a fundamental part of human existence. They can also be heavily politicized and socially significant. In the British Caribbean, white slaveholders were renowned for their hospitality towards one another and towards white visitors. This was no simple quirk of local character. Hospitality and sociability played a crucial role in binding the white minority together. This solidarity helped a small number of whites to dominate and control the enslaved majority. By the end of the eighteenth century, British metropolitan observers had an entrenched opinion of Caribbean whites as gluttons. Travelers reported on the sumptuous meals and excessive drinking of the planter class. Abolitionists associated these features of local society with the corrupting influences of slavery. Excessive consumption and lack of self-control were seen as symptoms of white creole failure. This article explores how local cuisine and white creole eating rituals developed as part of slave societies and examines the ways in which ideas about hospitality and gluttony fed into the debates over slavery that led to the dismantling of slavery and the fall of the planter class. Click here

Full text of accepted manuscript: Petley – Gluttony and Excess

Call for Papers

The ACH is pleased to receive paper and panel applications for next year’s conference. Members suggested several themes at this year’s Annual General Meeting in Martinique. While papers on these ideas are encouraged, applicants are welcome to submit proposals about other subjects or ideas. Click here for full details about the themes and information about how to submit a proposal.

New Look News and Posts

The S&R site has a new look for news items and blog posts. Watch this space for more updates!

Nelson and Slavery

Listen to Christer Petley’s paper about Horatio Nelson, slavery and the Caribbean. It was presented to a conference about the Royal Navy and the British Atlantic empire, hosted by the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth. See the letter that Nelson sent to Simon Taylor here.

British Slave Emancipation in France Antilles

An interview about slave emancipation in the British Caribbean with Christer Petley for the newspaper France-Antilles. Click here for a link to the article.

Royal Navy and the Caribbean

At a conference in Portsmouth next week, Christer Petley will discuss connections between the Royal Navy and slavery in the Caribbean, focusing on the relationship between Horatio Nelson and Simon Taylor. See this part of the S&R site to view the letter that Nelson sent to Taylor and which William Cobbett posted in his Political Register in February 1807, as part of a last ditch effort to stall the Abolition Bill as it passed through parliament.

Successful Conference!

Thanks to the Association of Caribbean Historians for an excellent annual conference in Martinique! It was good also to get to see the awesome Mont Pelée. Click here for more on its devastating eruption in 1902.