3.5 Behavioural factors data

Data on behavioural factors describe the behaviours of the study population. These include lifestyle choices such as smoking and drinking, and socioeconomic circumstances such as education and employment.

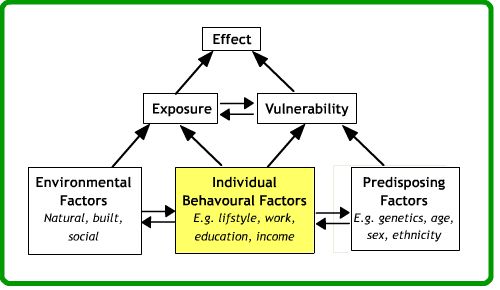

Individual behaviour represents one of the major influences on health experiences. It is well-recognised that some occupations carry specific health risks such as silicosis in mining, quarrying and other industries resulting from the inhalation of crystalline silica and that smoking is the second major cause of death in the world (World Health Organization). In order to further investigate the impacts of individual behaviours on health outcomes it is necessary to obtain data which link behaviour with health. Wilson and McDonald (1994) demonstrate that even within medical records kept by family doctors, the quality of information held about patients’ behaviour is limited and may be of variable quality.

There are various potential sources of health and lifestyle data. Medical records will contain a limited amount of lifestyle information and may particularly focus on smoking and alcohol consumption although this information generally remains confidential at the individual level and is often not recorded systematically. Population data sources such as censuses contain very little health information, and this is of course self-reported. Although they contain extensive information on important topics such as employment and housing they do not generally contain questions directly related to lifestyle. The third approach is through purpose-specific health and lifestyle surveys. These generally provide much fuller coverage of health-related topics such as exercise and diet alongside health information which may be self-reported, directly measured or a combination, but the population coverage of individual surveys is usually small. There is thus no single ideal data source that provides geographically extensive coverage at high sampling fractions on health-related behaviour and health outcomes. A fourth option, available only to researchers with access to individual-level records and working within an appropriate legislative framework, is the linkage of records between different data sources that allow investigation of health and behavioural factors from different data sources.

An emerging way of linking behavioural data with health information is the use of ‘data mining’ of keyword searches on the web. Probably the best known example of this was Google.org’s Google Flu Trends project, now shelved, which investigated the relationship between words used as search terms (e.g. ‘cold’, ‘sore throat’ and so on) and reported influenza cases in several developed countries. Although tracking key words can predict upsurges in influenza more quickly than more traditional methods, obtaining a detailed geographic picture of influenza (drilling down below state level) remained challenging and the project was withdrawn following criticisms of its predictive performance. We include a reference below (Kandula and Shaman, 2019) that looks back at the Flu Trends initiative and re-evaluates it.

Use of health surveys is illustrated by the papers by Oyebode et al. (2014) in relation to the Health Survey for England and by Mekonnen and Mekonnen (2003) in relation to Ethiopia. Although there are numerous studies based on such survey information, the development of GIS applications using these data is relatively rare, due to the limitations of spatial resolution in published survey data.

Activity

Review the surveys listed in the ‘Selected health and lifestyle surveys’ table and identify their coverage (in terms of target population and actual sampling fraction), scope (in terms of topics covered) and geographical resolution. Use the Internet (and / or references provided) to locate information on one further survey – if possible one that relate to the country or region in which you live. See if you can identify how the data from the survey are represented spatially. Can you locate groups of households or even individuals on the map? Post up a brief message to the course discussion forum, describing your survey and how readily the data from it could be used within a GIS.

The following table provides outline information on a selection of health and lifestyle surveys from the UK. In general terms, the degree of geographical detail available is greater in developed countries, but details vary significantly between individual surveys.

Table 1. Selected health and lifestyle surveys

| Health survey for England | https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england | National survey of adults and children |

| Scottish schools adolescent lifestyle and substance use survey | http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Public-Health/SALSUS/ | National survey of teenagers |

| Gateshead health and lifestyle survey 2016 | https://www.gatesheadjsna.org.uk/article/6211/Headline-data | Local survey of adults |

References (Essential reading for this learning object indicated by *)

Oyebode, O., Gordon-Dseagu, V., Walker, A. and Mindell, J. S. (2014) Fruit and vegetable consumption and all-cause, cancer and CVD mortality: analysis of Health Survey for England data Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 68, 9 Available online at https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-203500

Demographic and Health Surveys database (https://dhsprogram.com/data/) contains an extensive listing of health surveys in developing countries.

Mekonnen, Y., and Mekonnen, A. (2003) Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services in Ethiopia Journal of health, population and nutrition 21, 374-382 https://www.jstor.org/stable/23499346

* Wilson, A., and McDonald, P. (1994) Comparison of patient questionnaire, medical record, and audio tape in assessment of health promotion in general practice consultations British Medical Journal 309, 1483-1485 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.309.6967.1483

The Google Flu Trends project – now no longer an active Google project – is re-evaluated here:

Kandula, S. and Shaman, J. (2019) reappraising the utility of Google Flu Trends. Plos Computational Biology 15(8): e1007258 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007258

…and also here:

Ginsberg, J., et. al. (2008) Detecting influenza epidemics using search engine query data. Nature 457, 1012-1014. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v457/n7232/full/nature07634.html