Some general information

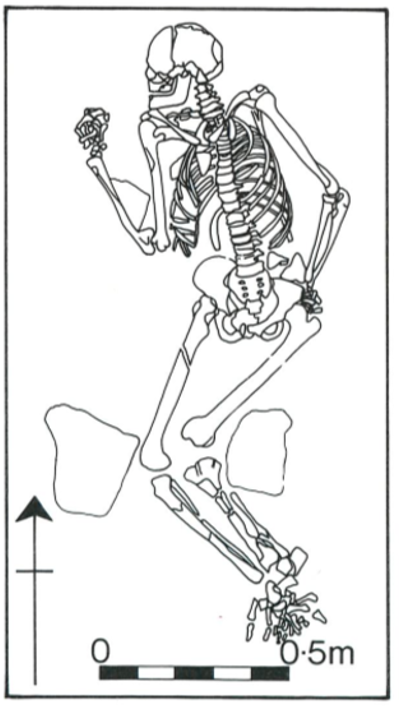

The skeleton was found as part of an excavation in the area surrounding the Southampton castle. It was found laying on its back, with the arms and legs partially flexed towards the right side, as shown in the figure below.

Based on the pelvic and cranial morphology as well as the size and robusticity of the bones, the individual was hypermasculine. The age at death was probably 37 plus or minus 3 years, while the estimated height is 169 plus or minus 3 cm. The skeleton is almost complete and found very well preserved. It is likely he was quite a gluttonous individual: all teeth are present, but there are small cavities in a few teeth due to dental caries.

His life in Southampton

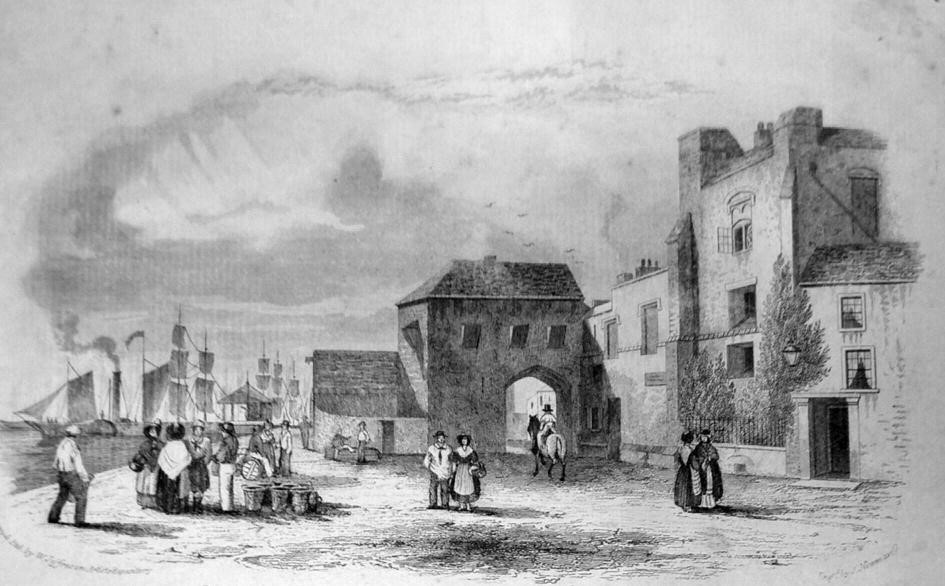

He probably lived in the late 13th or early 14th century, as confirmed by the pottery found in the same excavation. At that time, Southampton economy was mainly based on import/export of goods; in fact, the town was one of England’s prime ports.

However, such an intense economic activity also made it a target for raiders, as the Sotonians found out one morning in October 1338.

The French raid

At that time England was at war with France. One morning in October 1338, enemy ships silently sailed up Southampton water and dropped their anchors near West Quay (the actual old quay). As the city had no town walls yet, West Quay was undefended, though constantly used by the merchants for their trades. The French took full advantage of this.

Under the control of the King of France, the raiders stormed the town. Shops were robbed, houses were burnt, innocent people were murdered and the town’s resources were stolen. Southampton was left a smoking ruin.

The injury

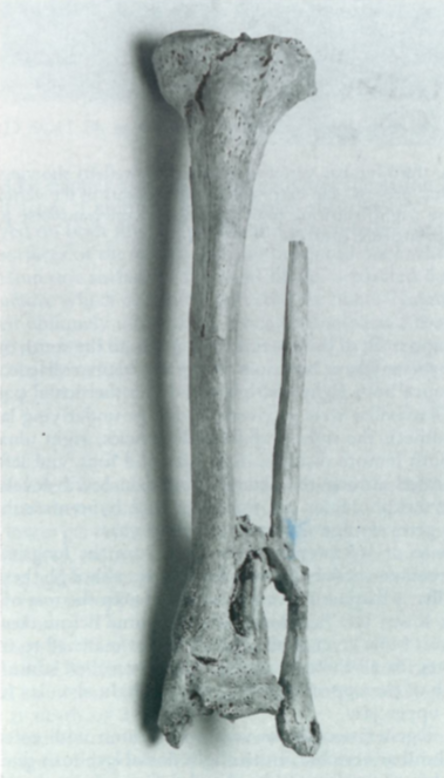

As a result of the French Raid, it is possible that the man injured himself while running away from the raiders. Studies found that the distal tibia and fibula on the left side were fractured by a force probably directed in a vertical direction, such as one that would result from landing on an extended leg. Therefore, it is possible that he injured himself while running away.

In the figure below, it is possible to see that the fragments were immobilised by a bony callus, simultaneously fusing the fibula to the tibia at the proximal end of the fracture region.

The difference between damaged tibia and the healthy one, belonging to the same skeleton, can be seen below:

Additional evidence of trauma is present in the lumbar spine, in both the third lumbar vertebra and the second lumbar vertebra. These fractures show a degree of healing consistent with that found in the left tibia, and it is likely that both the leg and spine were injured in the same incident.

Although it is not guaranteed that the injury had fully healed, a full engineering analysis has been done to assess whether the man would have been able to bear weight.

Southampton after the raid

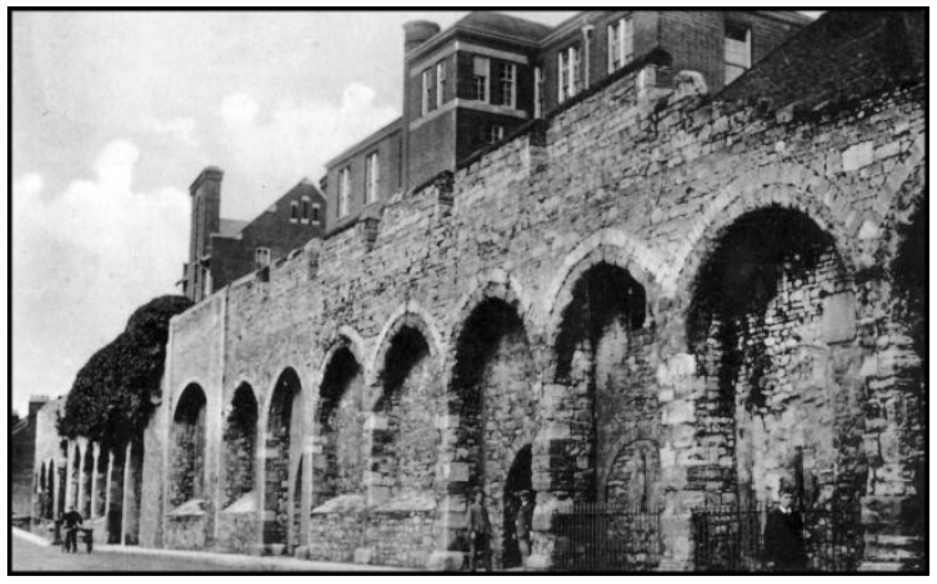

King Edward III ordered that the town was to be completely enclosed in stone walls to protect it from any future threats. However, the raid had damaged Southampton’s economy so much that this order could not be carried out immediately.

It was only in the 1360s that the walls started to be built. The town was to be fully enclosed, especially along the western quays, where wealthy merchants had built their houses. Of course, the merchants did not want to lose their sea front warehouses, but by 1380 doors and windows were blocked up with stone and converted into arrow slits and gun ports, becoming part of the town’s walls.

The man’s life after injury

Considering the conditions in which Southampton was left after the raid, the man probably lived miserably for the rest of his life. No sign of associated formal burial activity was found, which let us think he did not die with his family or relatives by his side.

Despite having fractures at both one tibia and two vertebras, the result from analysis suggest that he might have been able to walk. However, according to the archaeologists, it is likely he only survived a few weeks after the accident. This may be because the fracture got infected.