Month: December 2017

Intellectual Property undergraduate students participate in contest

Intellectual property undergraduate students took part in a contest organised by their lecturer, Dr Eleonora Rosati(Associate Professor in IP law) which consisted of analyzing a recent High Court decision on copyright protection for TV formats.

Three LLB finalists received prizes for their efforts: Diane Pham-Minh will have her piece published as a Current Intelligence note on the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice (Oxford University Press, edited by Dr Rosati); Paul Musa had his piece published on specialist copyright blog The 1709 Blog; and Sebastian Vogg had his piece published on the official Southampton Law School Blog.

Student Paul Musa said of this opportunity: “The contest enabled me to improve my analytical and researching skills. I particularly enjoyed examining the practical significance of this case, as it is going to have a huge effect on how the media industry operates”.

Sebastian Vogg, who was published on this blog, said: “As an exchange student, joining the IP writing contest was a very important experience for me because I learned to express myself more precisely and I made a big progress in using and understanding the legal sources of this country. That my article got published gives me a lot of confidence for my next challenges”.

Diane Pham-Minh said “I enjoyed analysing this case as I had previously studied the “Green” case, which formed the basis for this decision, when I was on my year abroad in Singapore. It was really exciting to see how the law has evolved, to actually write about it and later be published in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice.”

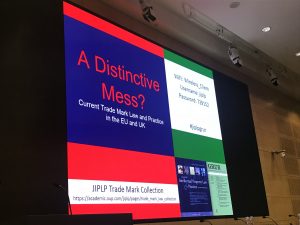

Law students visit Allen & Overy IP Law conference

On 24 November 2017, in her capacity as Editor of the Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice (Oxford University Press) and together with the German Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property (GRUR), Dr Eleonora Rosati (Associate Professor in IP Law) organized a conference held at the London offices of Allen&Overy to discuss the most recent developments in EU and UK trade mark law and practice.

The event consisted of two panel discussions featuring leading experts in this area of the law, and included a keynote address by Sir Richard Arnold (High Court of Justice – Chancery Division).

Several Southampton students – both current and past – attended (in the picture together with Eleonora), and had the possibility to discuss relevant issues with the over 300 practitioners, academics and students active in trade mark law who were also present at the conference

The features required for a TV format to be protected by copyright

What is it required for a TV format to be protected by copyright under UK law? The High Court of England and Wales answered this question in its recent decision in Banner Universal Motion Pictures Limited v Endemol Shine Group Limited, Friday TV AB and NBC Universal Global Networks UK Limited [2017] EWHC 2600 (Ch) (19 October 2017).

Southampton Law School visiting student Sebastian Vogg explains it all.

Here’s what Sebastian writes:

“In its decision of 19 October 2017, the High Court of England and Wales dismissed the claim of Banner Universal Motion Pictures Limited (‘BUMP’) for subsistence and infringement of copyright of the television game show format ‘Minute Winner’ because it was lacking the features required to be qualified as a dramatic work within the meaning of sections 1(1)(a) and 3(1) of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 (‘CDPA’).

Background

Mr Banner, the founder of the claiming company BUMP, devised a television game show format called Minute Winner. The information concerning this format was written down in a document (‘the Minute Winner Document’) and allegedly disclosed to the defendants by Mr Banner in circumstances that gave rise to an obligation of confidence.

According to BUMP, the defendants misused this information by broadcasting a game show called ‘Minute to Win It’ eight years later without Mr. Banner’s consent. BUMP claimed that this show was derived in substantial part from the Minute Winner format. The plaintiff argued that the Minute Winner Document was protected by copyright as a dramatic work and that the defendant’s unauthorized use amounted to copyright infringement. The format was not alleged to be a literary work, because dramatic and literary works are mutually exclusive categories. Hence, it is not possible to claim that a work falls within the scope of both categories. BUMP also claimed for breach of confidence and passing off. It should be mentioned that Mr. Banner had already tried similar claims before the Swedish courts and could not succeed.

Analysis

The Court had to decide upon the defendant’s appeal for summary determination of the claim and/or for it to be struck out, among others, because the contents of the Minute Winner Document did not qualify for protection as a copyright work. In terms of the summary determination, according to Part 24 (2) Civil Court Rules, the Court had to answer the question if there was a real prospect of succeeding. To do so, the Court had to assert if there was a real prospect of qualifying the format contained in the Minute Winner Document as a dramatic work.

The Court first determined what a dramatic work is. The CDPA provides no definition of dramatic work but in Norowzian v Arks Limited (No 2) [2000] EMLR 67 (at 73) it was held that a dramatic work is ‘a work of action (…) which is capable of being performed before an audience’. It should be borne in mind that no episode of the Minute Winner had ever been produced. Therefore, the question was if a television format is separately capable of being performed. The Court considered, among others, the decision of the Privy Council of New Zealand in Green v Broadcasting Corporation of New Zealand [1989] RPC 700 (‘Green’) as leading authority. In this decision, the format of a talent television show was not qualified as a dramatic work because it was lacking sufficient certainty of subject matter and unity to be capable of being performed (Green, at 40).

In the present case, the Court held that the relevant authorities indicate that qualifying a television format as dramatic work is, principally, at least arguable. The fact that there are spontaneous elements and changing events in every show, derived from the format, was not necessarily seen as a barrier to copyright protection.

In consideration of former authorities, the Court listed two minimum requirements for copyright protection. Firstly, the format must contain a number of clearly identified features which, taken together, distinguish the show from others of a similar type. Secondly, those distinguishing features must be connected with each other in a coherent framework which can be repeatedly applied so as to enable the show to be reproduced in recognisable form. So, if a show was produced by using the Minute Winner format, it must have been possible to distinguish the outcome from any other game show. As well, it must have been possible to recognise all episodes derived from this format as belonging to one concept.

The features of the format in the present case were basically: the title Minute Winner, the catchphrase ‘one minute to win (something)’, and the idea to give people the chance to win prizes by fulfilling tasks within one minute. Four examples of possible tasks and prizes were listed in the Minute Winner Document. The Court qualified these features as not capable of making a show distinguishable because they were part of the basic concept of almost every television game show. Furthermore, it was held that there was a lack of determining where the show should take place, how the contestants should be chosen, what type of one-minute tasks should be played, how long the show should take, and what kind of prizes should be winnable. Due to the lack of such elements, the Court couldn’t see any recognisable or repeatable structure of the format. According to the Court, the four examples of the document were too inconsistent to derive any structure of the show from them.

Therefore, the format had no realistic chance to be qualified as a dramatic work. For the case that this conclusion was wrong, the Court also held that the Minute Winner format and the show broadcasted by the defendants were different in almost all aspects and that there would have been no infringement anyway. The claims for breach of confidence and for passing off were also dismissed. The former mainly for reasons of jurisdiction rules, the latter due to BUMP’s missing goodwill.

Implications of the decision

In Green (at 25-45) there was some scepticism that a television show format could be qualified as a dramatic work. Anyway, it did not say that it was generally impossible. The possibility to qualify a format as a dramatic work was indicated in Meakin v BBC [2010] EWHC 2065 (Ch) (para 31) where it was assumed that copyright subsisted in specific television show formats. In the present case, the Court explicitly held that it can be possible for such a format to be protected by copyright as a dramatic work.

The arguments why the Minute Winner Document was not a dramatic work demonstrate which requirements could increase the chance of a format to be qualified as copyright protected. It seems hard for a Court to deny the copyright protection of such a format in a future case if it fulfils the requirements that were missed in the Minute Winner format. According to the present decision, criteria to take the threshold of the minimum requirements for copyright protection are: giving exact information about the possible contestants, the winnable prizes, the duration of the show, the kind of games, and where these games take place.

Like in Green (at 40) the Court explained its reluctance to qualify the format as a dramatic work with the argument that copyright creates a monopoly. This demonstrates again that the features of a format should be described as precisely as possible. The more exact these features are described, the less a monopoly would affect the rest of the world and the less it could be an argument against granting copyright protection. The Court held that BUMP could not claim a monopoly on games being played against the clock for one minute. In contrast, there could hardly be seen any problem if people were, for example, just kept from playing certain games, in certain places, to win certain prizes in a television show.

The Court pointed out, that there would have been no infringement anyway, because the format and the show broadcasted by the defendants were different in almost all aspects. One could say that this statement is kind of paradox because the Court first qualified the features of the format as not distinguishable and then used these features to make a precise distinction between the format and the defendant’s show. Of course, this conclusion was just made for the case that the Court was wrong in not qualifying the format as a dramatic work. But the mere possibility of reaching this conclusion implies that the features are distinguishable. A similar problem was, in terms of Green, already mentioned in David Rose, ‘Format rights: a never-ending drama (or not)’ (1999) 10(6) Ent. L.R. 170 (page 171).

The present decision brings no radical change in the assessment of television formats in terms of copyright law. But it probably provides a useful guideline how to draft a format that is likely to be qualified as being protected. The Court also emphasized that the relevant assessment is heavily fact-specific. Thus, if someone devises a format by following this guideline and lodges a similar claim in the future, there could be a different outcome than in the present case.”